Frederick Brooks wrote in The Mythical Man Month that “adding manpower to a late software project makes it later”. This is also known as Brooks’ Law. One of the reasons for this is that each time you add more people to a project, the communication overhead increases.

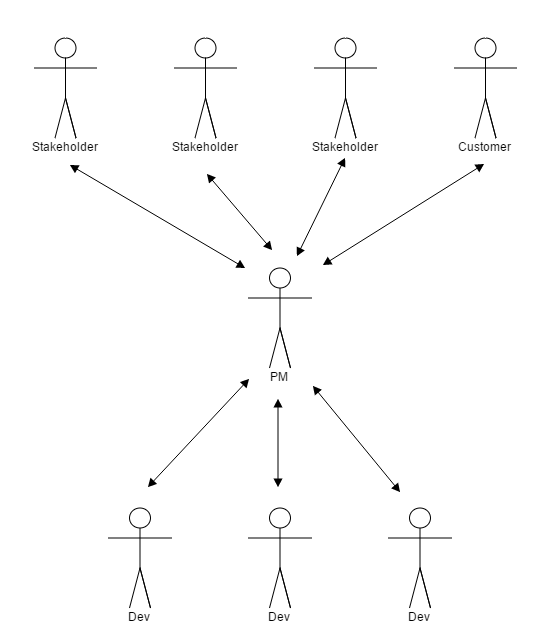

Here’s why: Imagine your entire team needs to work on a new feature. To be able to work on that feature, they need to understand what to build and how to coordinate building it. This requires sharing context. When you have a team of one, that team member does not have to communicate with any other team members. When you have a team of three, there are three people that need to coordinate. But if you increase the team to eight people, there are twenty-eight paths of communication to make to coordinate work. This image from a stackoverflow post explains the concept well:

Obviously there are advantages to having teams larger than one, otherwise every team would be a team of one. A team of one has to wear many hats. For example, a developer will have to gather requirements if a product manager is not doing it on their behalf. That might make sense sometimes, but any time spent gathering requirements is time not spent developing. It almost always takes more time to develop features than to gather their requirements and not everyone can develop. Therefore, the team as a whole would produce more if the developer(s) could spend their full day developing.

There’s also the issue with the bus factor. If a team of one quits or gets sick, progress abruptly stops. If there are multiple developers with a shared context, the others can fill the role of the absentee.

So how do you know when a team is too large and should be split? That’s not an easy question to answer. Obviously if developers are spending more time communicating than developing, the team (or its boundaries) are too large and should be split. And if the communication overhead negates the benefits of a larger bus factor number, the team should be split.

I don’t have better heuristics than this, I’d like to hear your ideas. But, I do have some suggestions on reducing the cost of the communication overhead.

Clear goals and requirements are a must for the project. For example, each developer should know “why” they’re building the feature they’re building. If they don’t, they can’t read between the lines when requirements are vague. They’re going to have to communicate more to get clarification. Or, they’ll end up building the wrong thing and have to communicate more to build the correct thing later.

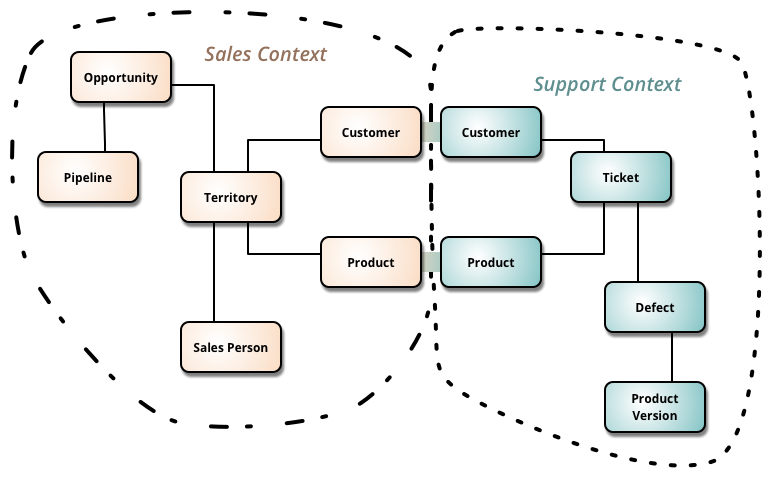

It helps if the team is working on a complete bounded context. If you’re unfamiliar with the phrase, that article should help and so should this image:

Imagine your project encompasses two bounded contexts like the image demonstrates. You’re going to frequently need to clarify which “Customer” and “Product” you’re referring to. That’s going to slow down communication.

It’s also important for the team to own a complete bounded context. If team X owns half of the Sales Context and team Y owns the other half, they’re frequently going to step on each others toes. Coordination will require a lot of inter team communication. This should also be considered when you’re thinking about how to divide a team that’s too large.

Another way to reduce communication overhead is to come up with a ubiquitous language. This means that when you’re working in the Sales Context, everyone is on the same page as to what a “Customer” is. This also means that the team agrees it’s called a “Customer” at all times. It’s not called a “User”, “Guest”, or “Patron” sometimes. This agreement will reduce the time it takes to communicate concepts. To learn more about Bounded Contexts and Ubiquitous Language, you should read Domain Driven Design.

Communication can be greatly reduced if there’s a communication gateway: A person where a lot of communication flows through so that everybody doesn’t need to communicate with everybody else. For example, if the Product Manager is the “requirements master” and that’s known to the team, I don’t need to ask the rest of the team for clarification of requirements. I can just go directly to the PM. I wrote more about this in my article titled, A Good PM is a Communication Gateway.

Last and least, if everyone has a high level of skill, the need to communicate is reduced. Imagine a new team member joins that doesn’t even know how to use the programming language of the project. A lot of communication will be required to catch that person up to speed.